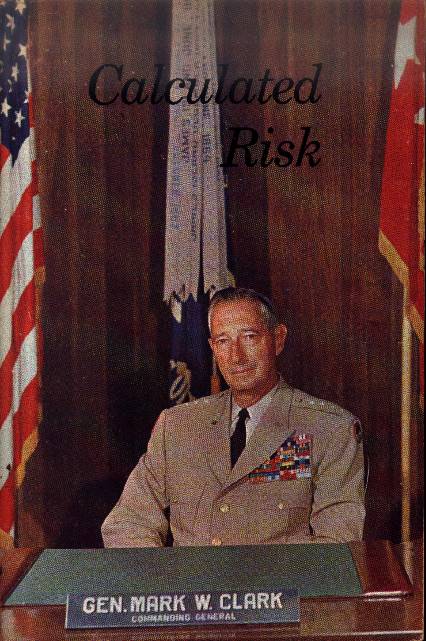

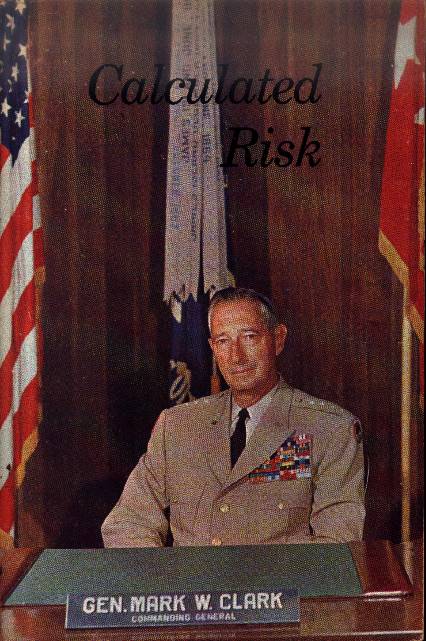

| Photo

Caption: General

Mark W. Clark, 11th President of The Citadel. (1954 - 1965)

Cover Photo from special edition of his book Calculated Risk, printed at The Citadel |

Gen. Mark Wayne Clark served as commander of United Nations (U.N). Forces in Korea from May 12, 1952, to October 7, 1953, and signed the Military Armistice Agreement on behalf of the U.N. Command with the North Korean Army and the Chinese People's Volunteers at Munsan-ni, Korea, July 27, 1953. The son of a career infantry officer, Clark was born in Madison Barracks, New York, and spent much of his youth in the Chicago suburb of Highland Park, near Fort Sheridan. With the assistance of his aunt, Zettie Marshall (the mother of Gen. George C. Marshall), Clark secured, at age 17, an early appointment to the U.S. Military Academy. A tall, lean, and often sickly youth, Clark failed to distinguish himself at West Point as either an athlete or scholar, graduating 110th in a class of 139 in 1917. Following graduation, he was commissioned a second lieutenant and assigned to the infantry. Severe health problems, which troubled him throughout his youth, caused him to be hospitalized and set him behind his classmates. Nevertheless, he was promoted to captain in August 1917, and saw action with the 11th Infantry in France, where he was wounded in action and later decorated for bravery.

Returning to the United States in 1919, Clark held various peacetime assignments, speaking on the Chautauqua circuit in 1921, and assuming posts in the Office of the Assistant Secretary of War (1929-33), where he served as an instructor. Clark graduated from the Command and General Staff School at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, in 1935, and served as deputy chief of staff for the Civilian Conservation Corps, VII Corps area at Omaha, Nebraska, prior to entering the Army War College, from which he graduated in 1937.

In 1940, as World War II approached, Clark, a lieutenant colonel assigned to Fort Lewis, Washington, was on the verge of meteoric rise, in part due to his close acquaintance with George Marshall and his longtime friendship with Dwight D. Eisenhower. In August 1941, Clark was named assistant chief of staff for operations of the general headquarters, U.S. Army, and a month after the American entry into the war, Clark was appointed deputy chief of staff of Army Ground Forces, and less than six months later, chief of staff. In October 1942, Clark became deputy commander in chief of the Allied Forces in the North African Theater and subsequently planned the invasion of North Africa. Prior to the invasion, he made a secret trip by submarine to the North African coast to meet with friendly French officers in the German-occupied territories. Clark's personal account of this dramatic and dangerous rendezvous brought him considerable public attention. As deputy commander of Anglo-American invasion forces, Clark took into protective custody the opportunistic Adm. Jean Francois Darlan, the highest-ranking French officer in French North Africa, and induced him to renounce the Vichy government.

In 1943, Clark commanded the Fifth Army in the Italian Campaign, the first to be activated in the European Theater, leading the force in the capture of Naples October 1, 1943, and Rome on June 4, 1944. As commander of the 15th Army Group, comprised of American and British forces, he accepted the surrender of German forces in Italy and Austria in May 1945. In June of that year he was appointed commander in chief of the U.S. occupation forces in Austria, and U.S. high commissioner for Austria. He served as deputy to the U.S. secretary of state in 1947, and attended the negotiations for an Austrian treaty with the Council of Foreign Ministers in London and Moscow. In June 1947, Clark returned home and assumed command of the Sixth Army, headquartered at the Presidio in San Francisco, and two years later was named chief of Army Field Forces.

At the end of World War II, Clark stood with Eisenhower, Generals George S. Patton, and Omar N. Bradley as a leading American commander in the European Theater. While he was much admired by his personal staff, others found him self-seeking, vainglorious, arrogant, and too concerned about gaining publicity. In 1948, his superior, Gen. Jacob L. Devers, chief of Army Field Forces, evaluated Clark as "a cold, distinguished, conceited, selfish, clever, intellectual, resourceful officer. . . . Very ambitious." The general also noted that Clark "secures excellent results quickly" and gave him a "superior" performance rating. Although he held some of his British wartime counterparts in contempt, Clark managed to impress Churchill and other European leaders. Charles DeGaulle, oddly, called him "simple and direct," and Clark's blunt appraisal of the Soviets and his well-publicized calls for greater American military preparedness in the early years of the Cold War earned him more admirers than critics during his service in Austria.

Following the removal of Gen. Douglas MacArthur, Clark was named commander in chief, U.N. Command, and commanding general, U.S. Army Forces Far East, April 30, 1952, succeeding Lt. Gen. Matthew B. Ridgway. Clark had visited Korea in February 1951, as chief of Army Field Forces to observe combat conditions and meet with then Eighth Army Commander Ridgway, a West Point classmate. Ridgway urged Clark to intensify training in night combat, and after his return to the United States, Clark experimented with the use of searchlights and flares.

On his arrival in Tokyo to take command in May 1952, Clark was confronted with the military deadlock on the front lines, roughly along the 38th Parallel, stalled Armistice negotiations with the North Koreans and their Chinese allies, and a complicated and explosive prisoner of war (POW) situation. Clark advocated an offensive that would have included attacks on bases across the Yalu River, but his plan, which would have widened the war, was not approved. Faced with an enemy of superior numbers, Clark determined that U.S. lines could not withstand "being dented" by an enemy who was willing to make great sacrifices in manpower. When "dented," Clark had U.S. forces "roll with the punch" and then follow with a counterattack to take strategic positions. Meanwhile, the prisoner exchange issue, which had caused a suspension in the Armistice talks, was complicated by Communist agents within the U.N. POW camps. The month Clark took command, Chinese and North Korean prisoners at Koje Island rioted and took Brig. Gen. Francis T. Dodd captive. Clark noted "I hadn't bothered to ask anyone in Washington about POWs, because my experience had been with old fashioned wars . . . . Never had I experienced a situation in which prisoners remained combatants and carried out orders smuggled out to them from the enemy High Command." Clark approved use of overwhelming force to clear out the POW compounds, and "broke" two general officers responsible for bad judgment during the riots.

Following his election to the presidency, Eisenhower, as promised during his campaign, went to Korea, December 2-5, 1952, accompanied by Bradley and Secretary of Defense-designate Charles Wilson. Clark had prepared a "broad plan" for victory, but the president-elect never gave him the opportunity to present it. To a disappointed Clark it appeared that Eisenhower would seek an "honorable truce" once in office.

Early in 1953, Clark was authorized to bomb the North Korean capital, Pyongyang, hydroelectric plants along the Yalu River and other targets previously prohibited. Pyongyang was for all intents and purposes leveled. The air attacks on the North Korean hydroelectric system deprived that nation of electric power for two weeks. Clark persevered in the air raids in the face of muted protests from the British and French. His main purpose was to keep pressure on the Communists to sign an Armistice more on U.N. terms.

On Feb. 22, Clark, with approval from Washington, wrote to Kim Il Sung and Peng Dehuai proposing the exchange of sick and wounded prisoners. His adversaries, perhaps disheartened by the death of Soviet Premier Joseph Stalin March 5, and the prospect of a frustrated United States turning to atomic weapons, agreed to the exchange and suggested that this first move could "lead to the smooth settlement of the entire question of prisoners of war." On April 2, the Communists agreed to Clark's offer of a meeting of liaison groups and, in a reversal of their earlier stand, acceded to the use of a "neutral state" to ensure a just solution to the question of repatriation. The liaison groups met April 6 and Operation Little Switch began April 20. Six days later the first plenary session at Panmunjom since the previous October was held.

Clark now faced the task of persuading a reluctant President Syngman Rhee of South Korea to accept a compromise settlement. On April 27, Clark flew from headquarters in Tokyo to Seoul for a series of meetings with the strong-willed South Korean leader. Two days earlier, Rhee's ambassador in Washington had told Eisenhower that Rhee would withdraw Republic of Korea forces from Clark's U.N. Command if an Armistice allowed Chinese to remain south of the Yalu. Rhee was unresponsive to Clark's analysis that neither side had won the war. On May 12, Clark found Rhee still strongly opposed to a truce. Nevertheless, on May 25, the final offer of the U.N. Command was presented at Panmunjom.

Clark offered Rhee security assurances, U.S. financial aid and military assistance to build the ROK Army to 20 divisions. As the date for concluding the Armistice approached, Rhee made a last desperate move to disrupt the agreement. On June 18, he ordered 27,000 Communist prisoners who were awaiting a neutral party to determine their status to be released into the South Korean countryside. Yet, despite Communist protestations, diplomacy prevailed, Rhee was issued a stern reprimand by his American allies, and the agreement held. On July 27, 1952, at the 159th plenary session, an Armistice agreement was formalized. Believing himself to be the first U.S. commander to agree to an Armistice without victory, Clark signed the peace documents at U.N. Command advance headquarters at Munsan-ni, stating afterwards, "I cannot find it in me to exalt at this hour."

Clark relinquished his Far East command October 7, 1953, and retired from the service at the end of that month. He accepted the presidency of The Citadel in Charleston, S.C., a post he held until his retirement in 1965, when he was named president emeritus.

In 1954, he had been appointed by former President Herbert Hoover to chair a task force to investigate the Central Intelligence Agency and other intelligence organizations of the U.S. government. He wrote his memoirs, From the Danube to the Yalu (1954), and spoke frequently on the threat of Communism and the need for greater U.S. military preparedness. In the 1960s, he renewed the friendship with Eisenhower that had been strained during the Korean War.

Michael J. Devine

(Original Biography published

on the Internet at http://www.state.nj.us/military/korea/biographies/clark.html

A minor correction, as noted, has been made and an updated photo

added - REL)

Bibliography

Clark's papers (more than 60 boxes) are located at The Citadel.

Blumenson, Martin. Mark Clark: The Last of the Great World War II Commanders (1984).

Clark, Mark W, Limited War (The Citadel, Charleston: n.d.)

Holt, Daniel D. "An Unlikely Partnership and Service: Dwight Eisenhower, Mark Clark, and the Philippines," Kansas History (Autumn 1990).

Kaufman, Burton I. The Korean War: Challenges in Crisis, Credibility, and Command (1986).

Rees, David. Korea: The Limited War (1964).

Saxon, Wolfgang. "Conqueror of Rome," New York Times (April 17, 1984).

Reprinted with permission from The Korean War: An Encyclopedia, edited by Stanley Sandler and published by Garland Publishing, Inc.